ON THE SCENE: ‘Pianoforte’ and a world-class piano competition

Gary Smith, Sarah Patton and John Huttlinger (Provided photo — Naj Wikoff)

The documentary “Pianoforte,” presented by the Adirondack Film Society Friday night, March 15, at the Lake Placid Center for the Arts, was the third film in their “See Something, Say Something” series.

The film follows several gifted young pianists seeking to win one of the most prestigious competitions in the world: the XVIII International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition. This competition is held once every five years, though this one had been twice delayed by COVID.

Sixty highly rated pianists were selected out of a pool of several hundred applicants. Over the next three weeks, they were whittled down to the top 12, who vied for the five prizes awarded, most especially for first place. The top prize included 40,000 Euros and a year of performance; a professional career was launched.

The documentary went behind the curtain to share the level of practice, emotions, coaching and pressure the piansts and several other competitors who didn’t make the final cut were under. Following the screening, Richard Rodzinski of Lake Placid, who led another equally prestigious Van Cliburn International Competition for 23 years, led a post-screening discussion.

Rodzinski said that doing well in such competitions was not an end, such as in audition for a part in a play where you got the gig or not, but more like a stepping stone towards developing a career.

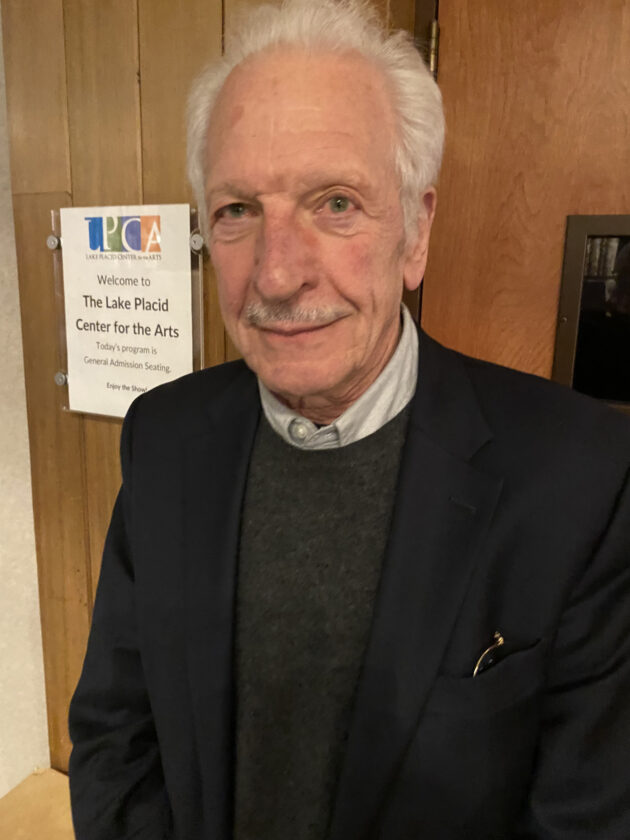

Richard Rodzinski (Provided photo — Naj Wikoff)

“Jury selections are like letters of recommendation,” said Rodzinski. “They are designed to identify the likelihood of how well these musicians will function in the real world. In a very real sense, they are applications for concert tours, recordings, and television appearances, basically, for a career.”

Achieving a spot in the top 60 is difficult as the criteria are high and the base is getting wider. In China alone, 60 million people are learning to play the piano, a boon for leading piano makers. At the Chopin competition, the participants must be professional musicians between the ages of 16 and 31 who passed through the preliminary round or won one of a list of prestigious competitions approved by the Chopin Committee. Also, all in the top 60 should have had experience playing in front of an orchestra.

As all the top musicians begin playing early, usually between 5 and 7, many arrive very experienced. During the film, one musician flipped through the pages of two large photo albums filled with copies of the plane, train and other tickets he used to get to competitions and performances. All applicants submit their applications, which include a resume and video(s) from which the 60 are selected by the qualifying committee for the preliminary round. At the competition, only works by Chopin are performed.

The competition then sifts into three stages; in the first, the 60 are reduced to 40; in the second, the 40 to 20; in the third, the 20 that year to 12, which move on to the final competition round.

The process is grueling, made more so by the presence of the pianist’s coaches and, unsaid, the documentary filmmakers. Rodzinski said a piano competition is a terrible way to select the top performers, but no one has found a better method. He also said that the cream, the top performers, will rise above everyone else; sometimes, the cream is thin, and sometimes, it’s fatter.

To play at the highest level, musicians have to be in good physical shape and willing to dedicate up to twelve hours a day to practicing, which takes a toll on their families and social lives. The documentary illustrated that the young musicians were their own harshest critics. However, the Russian coach stood out for her brutal approach, treating Eva Gevorgyan as if she were an amateur, while in reality, she was a young professional who had already received more than 40 awards at international competitions.

By contrast, the Chinese coach could not have been gentler, going out of her way to reduce the tensions and pressure with words of encouragement and shoulder massages, noting that she probably spent more time with her protege Hao Rao than his family members. At the same time, some of the competitors seemed to have lost a bit of their joy in performing under such a demanding schedule; indeed, one of the top candidates dropped out of the finals, not Leonora Armellini, who sat down to perform every time as if it was the thrill of a lifetime.

During the film, one coach quoted Rodzinski, who always shared three important lessons to follow: one, don’t play for the jury; play for the audience, a lesson he would repeat two more times. His message was, don’t try to please the jury by getting every note and position of the hand correct; instead, play a concert for the audience. As a jurist once told Rodzinski, “All I want to do is to fall in love with the music.”

Insights included watching the pianists select their instruments from about a dozen choices for the competition. In the end, all the top finishers were ravishing to hear, but in a way, it seemed odd that the film in no way celebrated the winner, which Rodzinski said was because they were all winners, all great musicians, all gained a lot of visibility by finishing so well. Yes, for one of them, their career got a significant boost forward, but all demonstrated that they were the best of their generation.

“Yes, you have first, second, and third prizes, but you recognize them all by awarding them all sizeable awards,” said Rodzinski. “Only time will tell who will end up with the greatest career.”

“The film and Richards’ comments allowed me to see behind the curtain,” said Gary Smith. “I had no idea; I’d never seen a piano competition. I enjoyed it immensely.”

“I wanted to know more,” said Sarah Patton. “What made one person better than another, but the film didn’t seem interested in informing you that way; it seemed more interested in conveying the competition. I wondered how much the coaches were playing to the camera. While I found it interesting, it could have informed me more. The film needed a Richard Rodzinski.”

“I thought it was excellent that you could see a film and hear from an expert on the subject matter the same night,” said Leo Mondale.

(Naj Wikoff lives in Keene Valley. He has been covering events for the Lake Placid News for more than 15 years.)