ON THE SCENE: My grandfather’s long walk to freedom

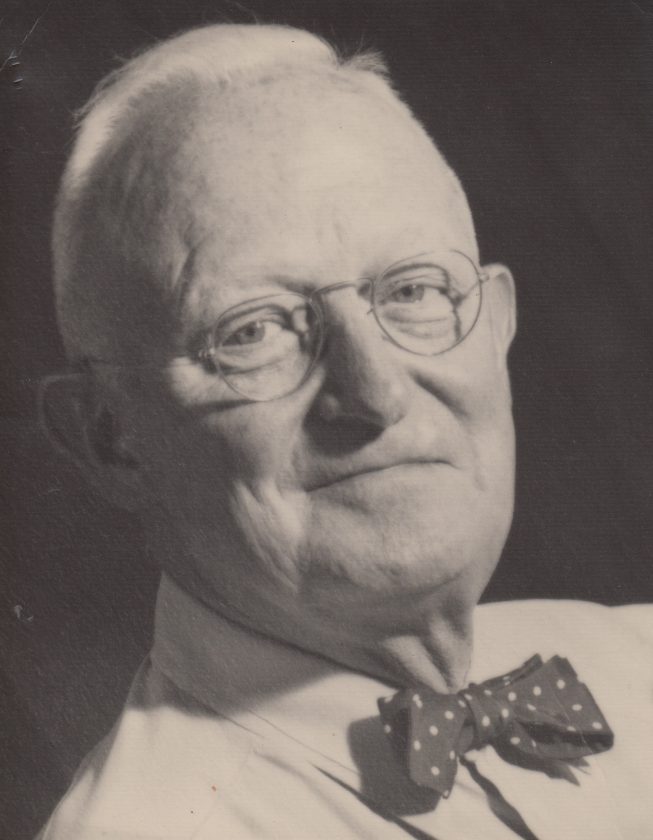

- Dr. Henry J. Gerstenberger (Provided photo — Naj Wikoff)

- Gretel, far left, and her sister Elselou, far right, at the Berlin Zoo in 1936 (Provided photo — Naj Wikoff0

Dr. Henry J. Gerstenberger (Provided photo — Naj Wikoff)

Over Thanksgiving, I started watching a disturbing though riveting PBS series on the rise of Adolf Hitler, the German politician and leader of the Nazi Party in the 1930s and 1940s. The series demonstrated how he took over and demolished a Democratic government within four short years — a situation that led to my grandfather, my Grosspapa, Dr. Henry J. Gerstenberger’s long walk to freedom.

In the years that led up to Hitler’s reign, Germany’s economy was collapsing and inflation was so out of control that the cost of food could double in a day. Contributing was Germany’s crushing war debt following the signing of the Versailles Treaty and the end of World War I. At the time, there was widespread dissatisfaction with the Weimar Republic (1918-1933) due to the failing economy and an aggressive disinformation campaign led by many in the conservative party and the military that the war was not lost on the battlefield but by traitors at home.

In the late 1920s, the economy started to recover, and support for right-wing conspiracies began to wane, but then came the world-wide financial collapse led by the 1929 U.S. stock market crash. The resulting downward economic spiral provided fertile ground for Hitler, the National Socialist Party leader, to gain traction by partnering with conservatives, fanning the flames of discontent and blaming others, the elite, intellectuals, gays and most especially Jews for society’s plight.

Hitler’s rise to power during this time is the focus of the PBS three-part series, “Rise of the Nazis.” His rise was made possible in part by conservative politicians who wrongly felt they could use him for their own ends, a belief that shattered when they realized too late the full extent of his ambitions and the ruthless power he had assembled. The series producers used historians, archival footage and reenactments to tell this story and paint a portrait initially disbelieved in the west and recognized and fought against by too few within Germany.

At the time, most countries’ political leadership was focused on the internal challenges of addressing their failing economies. In Germany, following hitler becoming chancellor in 1933, people saw the economy improve. It was driven by such initiatives as the privatization of many industries, public works projects such as the creation of the Autobahn — the most advanced highway system in the world — and more importantly, under the radar of many, the massive investment in military rearmament.

Gretel, far left, and her sister Elselou, far right, at the Berlin Zoo in 1936 (Provided photo — Naj Wikoff0

During this period, my mother, Gretel Gerstenberger, and her older sister Elselou arrived in Germany as part of a high school student exchange in 1932-1933 that included stops in Dresden, where many relatives lived. She and Elselou returned in 1936 for university year abroad in Munich. Before classes began, they attended the Olympic Summer Games. There they managed to get on the field taking pictures of such members of the U.S. team as Jesse Owens, his track and field teammates, and the fabled U.S. rowing team featured in the book “Boys in the Boat.”

I once asked my mother about the Nazi Brownshirts, and she said she and her classmates didn’t take them seriously, something they learned to regret. Meanwhile, her older sister met and fell in love with an engineering student, Hans “Fritz” Brinker. Fritz proposed, and Elselou agreed to marry. Eventually, they set a wedding date for August 1939, and he traveled to the U.S. for the wedding.

At the time, my grandfather, Dr. Henry J. Gerstenberger, was a founder and the first president of the Western Reserve Babies & Children’s Hospital, now known as Rainbow Children’s Hospital. He was world famous for his pioneering advancements in the treatment of children receiving many awards for his work.

Following his graduation from the Western Reserve Medical School in 1906, my grandfather continued his studies in the emerging field of pediatrics in Berlin and Vienna. There he contracted tuberculosis. His parents felt he should take treatment in Germany and Austria, centers of the most advanced medical care in the world, which, coupled with spending much time in the outdoors, led to his recovery. Returning home, he was named head of pediatrics at the City Hospital and Western Reserve Medical School and was soon appointed the founding director of Babies & Children’s Hospital.

As it happened, following the wedding of his daughter in August 1939, my grandfather was scheduled to travel to Berlin for a medical conference and offered to provide transport for his daughter and new son-in-law. They agreed as Fritz needed to get back to graduate school. They traveled on the S.S. Bremen. Upon arrival in Germany in late August, Dr. Gerstenberger’s colleagues shocked him with the news that Germany was about to invade Poland within a week and that he had to leave Germany immediately. Returning by ship was not possible as all travel to the U.S. was canceled.

Meanwhile, Fritz was denied permission to travel, as was his new bride, my Aunt Elselou. Urged on by his colleagues, daughter, and son-in-law, my grandfather realized that his only option was to walk south in the hope of reaching France or Italy and a ship to the U.S.

Abandoning his luggage, wearing his business attire and street shoes and carrying his doctor’s bag and whatever else, he headed south. He walked mostly at night depending on strangers’ kindness, his ability to speak several dialects of German, and bartering his medical skills. Remarkable, with Germany now on a war footing and security radically tightened throughout the country, no one turned him in, and he was able to sneak across Germany’s southern border.

Astonishingly, 40 days later, having walked the length of Germany, the western end of Austria, Lichtenstein, Switzerland, the Alps, and Italy’s Liguria Alps, my grandfather made it to Genoa, Italy, a journey of well over 1,200 kilometers. There, his wife was able to wire funds so he could travel home on a freighter.

Fritz survived the war and was able to reconnect with my grandfather, who was able to help arrange his immigration to the U.S. Aunt Elselou died in Germany.

For my grandparents, my mother and her sisters, the experience was a shocking wake-up to the realities of Nazi Germany. At the time, American reporters stationed in Germany in the years up to the outbreak of war, Jewish communities and their advocates, and refugees tried in vain to warn the U.S. public and politicians. Unfortunately, few listened.

My grandparents lost a daughter, my mother her favorite sister and best friend, and all were shaken by how the Nazis took over Germany leading the country, its people, and so many others to ruin along with the atrocities of the Holocaust.

I had hoped two years ago to replicate my grandfather’s walk on what would have been the 75th anniversary as a way of honoring the many people who risked their safety to provide him food, places to say, and no doubt improvements to his clothing. But last-minute work conflicts prevented me from taking time off.

At this point, I’m thinking in three years for the 80th anniversary, knowing full well I couldn’t replicate his speed.

(Naj Wikoff lives in Keene Valley. He has been covering events for the Lake Placid News for more than 15 years.)