ON THE SCENE: Remembering Harriet Tubman

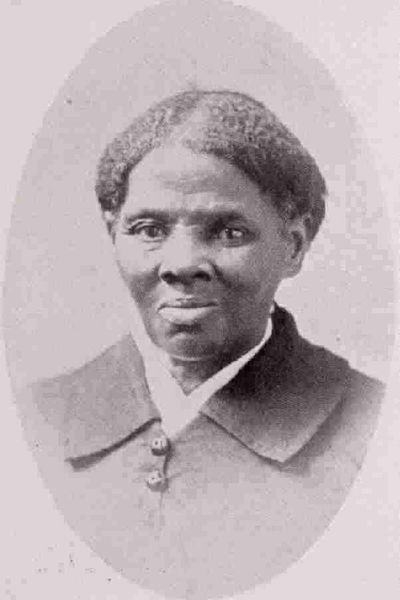

Harriet Tubman

Abolitionist John Brown held former slave Harriet Tubman in high esteem. Brown called her General. Harriet was but five feet tall.

While short in stature, she was physically and mentally tough returning to the South thirteen times to lead 70 enslaved friends and family to freedom. Tubman served as a nurse and spy for the Union Army, and was the first woman to lead an armed assault during the Civil War and, while so doing, helped free over 750 slaves.

As well as an abolitionist, Tubman was a suffragist activist working closely with Susan B. Anthony and Emily Howard, speaking out for women’s rights in New York, Boston, and Washington amongst many other locales, and later donating the land for the construction of the first home for the elderly poor in the United States.

Tubman was born circa 1882 as one of nine children to slave parents on a large Maryland plantation and worked in the fields and forests driving oxen, plowing fields, and hauling logs. When young she was beaten badly, once with heavy weight that damaged her skull resulting in headaches, epileptic-type seizures, and visionary dream experiences throughout her life that, as a devout Christian, she experienced as revelations from God.

The knowledge gained from her escape from slavery in 1849, and subsequent trips to free others gained her the honorific “Moses,” by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, combined with her passion, courage, skill, and religious fervor resulted in an instant bonding with John Brown when they met in April 1858, each of whom felt their meeting was a result of divine intervention.

Site manager Brendan Mills talking to the students at the grave of John Brown and the raiders (Photo — Melissa Yandon)

For Martha Swan, founder and director of John Brown Lives!, and a teacher at Newcomb Central School, their partnership provided the opportunity to connect Newcomb students to two of the major figures of the abolitionist movement, and with the students of a southern school, and in so doing, develop a more nuanced understanding of slavery in the North and South.

“The project is trying to accomplish a couple things,” said Swan. “One is to support teachers in the teaching of this very important history of ours, slavery, the struggle for freedom, the Civil War; to support them with top flight scholarship and access to scholars and historians, with support of one another as teaching collaboratives in the various schools, support and inspiration of the kids through the arts in particular, but also, writ large, is what we are working with teachers and school communities to rethink how we approach, the study, teaching, and our understanding of slavery, the Civil War, and the struggle for freedom.”

“We tend to approach that long, long chapter of our history as a Northern story and a Southern story. We in the North tend to have this sense of ourselves that we were all abolitionists, slavery was just a Southern phenomenon, that it wasn’t a Northern thing at all, and that the North was against slavery from the beginning to the end,” continued Swan. “Historically that’s just not true. I think that bifurcation of our history is really distorted and it gets us nowhere. It doesn’t get us to the place of understanding how foundational and fundamental slavery was to the development of the country including slavery in the North, smaller in scale in terms of numbers but not in terms of the economic engine that slavery drove. In that regard it was very much a Northern institution. The big banks, the manufacturing, the markets for shipping sugar, tobacco, and so forth were in the North. The North is implicated in slavery in a way that we do not readily recognize and tend to teach. That’s the over arching goal, and what we really want to do is bring teachers and students in Northern and Southern schools in dialogue with one another about this history.”

Swan launched that dialogue around Harriet Tubman, who grew up a slave on a Southern plantation in Maryland, became active in the struggle to end slavery, lived in New York state, and was connected to our community and region through John Brown. The project has established a relationship with a school in Maryland located not far from where Tubman was raised, has included teacher training down there and here, and sponsored scholar and artists in residence in both locales. Future plans include collaborations with schools and resources in Auburn, New York, where Tubman lived and was an active suffragette, and in Canada, at a terminus of the Underground Railroad where members of Tubman’s family found freedom.

I first observed a class lead by Tom Thurston, Education Director at the Gilder Lehrman for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition at Yale, on how to find and use original source materials, such as ads for the sale of slaves or people seeking loved ones in the aftermath of the Civil War, to enable kids and teachers develop a more nuanced understanding of the reality of slavery.

Terry Leonino teaching the kids sign language (Photo — Melissa Yandon)

“I liked the workshop,” said middle school student Alex following Thurston’s presentation. “I learned that slavery was more horrible than I thought. I wish it never happened.”

“The documents gave us a much more personal understanding about slavery,” said Peter, another student.

“I have a six year old son and the idea of him being sold away from me and not being able to express my grief is very heartbreaking,” said Gemini Randal, who teaches 7th and 8th grade. “These source materials put a whole new spin on it history. Thinking that we in the North are absolved, I mean the people who made the ink, the paper, and printed the ads all profited off of slavery.”

Source materials examined with Thurston and Tubman/Brown biographies, researched and written by the kids were turned into lyrics and put to music under the guidance of musicians in residence Terry Leonino and Greg Artzner (aka Magpie) known for their one-act play Sword of the Spirit that tells of the life of John and Mary Brown. They also taught the students how to translate their songs into sign language incorporating it into their performance, songs that were subsequently copyrighted with contributions duly noted.

“The pebble we drop in the pond is Harriet Tubman,” said Swan. “Last year the kids really focused on her. This year they are looking at some of the other relationships and aspects of Tubman’s life. We try to have a geographical relevance because we want students to have a sense of ownership, that where they live things happened. By rooting an aspect of Tubman’s life to our region we help them get a sense of history and to understand some major events happened right here.”

“I went to a soccer game so I got home pretty late. I couldn’t think of anything, but then in the morning the line kind of came to me,” said Brayden of his contribution, the last line of the song ‘this war hasn’t ended, in fact it’s just begun’. “It was a result partially because of our visit to John Brown’s farm and knowing he was in jail before the end.”

“I really loved making a song,” said Evan.

“We are all having fun,” said Josh.

“I liked voting on what words to use in the song,” said Warren.

“I like how the song came out,” said Ozzy.

“This experience was phenomenal in every sense,” said Mrs. Slayback. “They are loving it, learning from it, and having so much fun. What I like the best is the collaborative piece because we are pulling in the special education teachers with the regular Ed teachers, the music and the art, and everyone is reinforcing each other. The kids are learning so much and everyone is having a ball. We had a really nice turnout by the parents and they too had a ball. We are so excited that we are right now preparing a similar unit for next year. Terry and Greg, wow. Their presence reinforces everything we do in our writer’s workshop except they do it about twenty times faster than we do it. It’s been a wonderful experience.”

“We are teaching history through creative songwriting,” said Greg Artzner. “It’s an exercise in arts integration. The process of creative songwriting is a multi-faceted process of English language arts and English language education. We are teaching all kinds of different things in addition to using reference books and what the students learn through doing research and source materials. We are here to facilitate the process of writing lyrics and then bringing the music in. We are here to get every single one of the kids to participate in one way or another.”

“We give the schools involved a copy of all the songs we create,” said Terry Leonino. “We hope to do a CD of all the songs because they each tell different stories and different perspectives that together tell a much fuller story of who Harriet was. Most people think of her connected to the Underground Railroad, and nothing ever happened afterwards. They don’t know that she was such an incredible activist. Her life was about being a Union spy so she could continue to end slavery, being a woman suffragist so she could continue to elevate women, being a person who started the first hospital in the country for people who had no money, which she called John Brown Hall, and the first place for people to live who had no money who were frail and old, the first elderly home, the first nursing home that we now have all over the country. That one woman did all that. Not bad. It’s good that she lived until she was 90 because she had a lot of time and did not waste one minute of it.”

“At the very end, the most incredible thing about these kinds of experiences is what radiates and rises up out of the kids is something they are going to use their whole life,” said Terry Leonino. “Whether it is economy of language, literacy skills, a love for music, a love for a story, or a love for history, they are going to get so many things from this one experience.”

“Here we are teaching and dealing with one of the most painful histories of the human experience but in a way that is joyful, life-giving, and makes all of us want to learn more and not avoid this really, really painful chapter of our history that is so difficult to talk about,” said Swan.

- Site manager Brendan Mills talking to the students at the grave of John Brown and the raiders (Photo — Melissa Yandon)

- Terry Leonino teaching the kids sign language (Photo — Melissa Yandon)