ON THE SCENE: Nathan Farb returns to Russia after 41 years

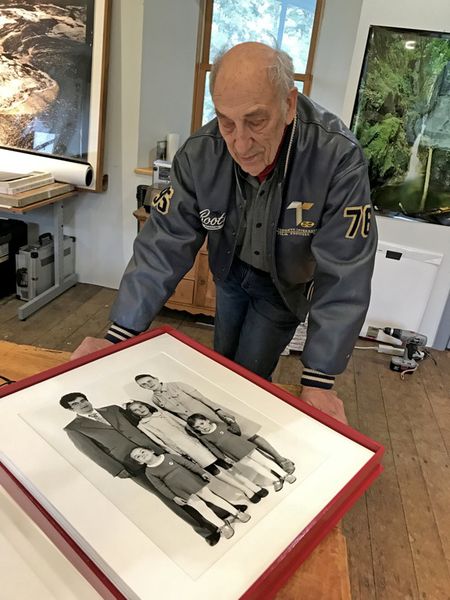

Nathan Farb looks at a photo he took in 1977 of Svet, her sister and their parents. (Provided photo — Naj Wikoff)

Forty-one years ago, photographer Nathan Farb, of Jay, traveled to the Siberian city of Novosibirsk, a major cultural center and the third most-populated city of Russian after Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Leonid Brezhnev had just been named chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, so was serving as head of both the State and the Communist Party. Brezhnev was the state’s most powerful leader since Stalin. Secure in his combined powers, Brezhnev had sought to increase cooperation and trade with the United States. And this had benefited Farb.

Novosibirsk party leaders agreed to host an exhibition of American photography in cooperation with the U.S. Information Agency, then promoting American culture overseas. Farb sought and received permission to travel with the exhibition as its guest photographer and take photographs of citizens attending, this at a time when taking photographs of Soviet life was strictly forbidden.

His pitch was that he’d be showcasing Polaroid film that printed images instantly; he’d give the prints to the people he photographed.

Each time Farb took a photograph, he peeled off and tossed away its paper backing before giving its subject the print. What people didn’t realize is that the discarded backings that Nathan retained and shipped back to the U.S. in a diplomatic pouch were high-quality 3×4- and 4×5-inch negatives from which he would later print large images and, ultimately, a book titled “The Russians.”

Farb photographed hundreds of Russians from all walks of life in Novosibirsk. With so many people jostling for their free print, he usually had only one chance to get his shot right. Get his shots right he did, with several images going on to become part of the New York Museum of Modern Art’s collection. A couple of years ago now, Farb’s Russian photographs were again being shown in the U.S., including by SUNY Plattsburgh and the California Museum of the Cold War, exhibits that led to The New York Times writing a blog on Farb’s work.

Andrei Fillimonov, a Russian poet and correspondent for Radio Free Europe’s Siberia Desk, now working out of Germany, saw The Times’s blog and called Farb. Fillimonov wanted to blog about Farb’s initial trip to Russia. After that got underway, Fillimonov pitched Farb on returning to Novosibirsk, this time with a German film crew covering the event. Farb was initially a bit ambivalent about the idea, thinking that his initial trip had been a once-in-a-lifetime sort of thing. He later reconsidered: the trip might be an adventure, an opportunity to do something new. And he agreed.

The German film team announced the project and posted his photos on social media. To Farb’s surprise, major Russian media outlets began to reach out to him for interviews.

As an outcome of the Russian media coverage, millions of people across Russia saw examples of the photographs that Farb had taken four decades ago. In Novosibirsk, the response was electric, as for the first time many learned of Farb’s treasure trove of photographs taken 41 years ago. Consequently, about 10 percent of those who had been photographed, or members of their families, began contacting Farb.

“I thought, oh, my God,” said Farb about a week before he departed on his return trip to Russia, “I am going back to meet and photograph some of these survivors. I’ll be in Novosibirsk for about a week. What I brought out of the Soviet Union in 1977 was a journalistic coup. It was tough to pull off. I thought something really interesting would come of it, but I hadn’t thought of going back, or anything like this. Two months ago, when I agreed to this trip, I was thinking, what can I do? What’s possible here? Now I am feeling much, much more connected. I’ve bonded with a lot of these people personally. Now have 30 or so new Russian friends.”

Farb showed me a photograph of two young girls and their parents. Pointing to one of the girls, he said, “Her name is Svet, short for Svetlana. She’s now all grown up. She’s now, like, 50. She recently wrote to me saying, ‘My sisters and I saw this photograph, and we cried all night.’ That’s because their mother is gone now. I immediately went to her page (in ‘The Russians’), and I saw that her mother was an old woman then. These people have led lives! For 40 years I’ve seen them as pictures, as art. They’re not; they’re people. My life has had an arch, with ups and downs. And every one of these people’s lives has had its life arch.”

When Farb photographed his subjects in 1977, he had no opportunity to come to know any of them as people. He took their portraits, handed them prints, and then they were gone. He didn’t speak Russian and, for the most part, they didn’t speak English. They had no sense that they were being photographed for any publication, so were relaxed. More often than not, their personalities shone through unguarded.

Many Americans know Farb for his carefully crafted, even deliberate, photographs of nature. Fewer people know that he spent much of the 1960s photographing street people in America. He became skilled at capturing moments, emotions, on film. He could see, frame and make aesthetic decisions quickly, a skill that paid off well in Novosibirsk.

Farb’s return to Novosibirsk in early November where he met many of the people, along with members of their families, whose lives he had had mere glimpses of in the past was an emotional experience for him. Just talking about it brought him to tears. On one level, he was surrounded, in Novosibirsk, by members of the press taking photos of him, something he hadn’t experienced before on that scale. On a more profound level, he reconnected with many people who, like him, were now 41 years older.

“Meeting each of these people whom I photographed over forty years ago was an amazing experience,” said Farb. “I didn’t anticipate how emotional it would be for both them and me. I didn’t expect it. It wasn’t like anything I’d ever done before. I didn’t have a clue!

“You know the picture of the chiefs-the party leaders? The guy on the far left who looks like a Cary Grant figure-you know, an American pilot, a Korean ace. He’s now a very old man. I learned his name: Nikolay Garoshuk. We embraced. I didn’t know that he had been one of the leaders who had wanted the American exhibit to come to Novosibirsk. At the time, I had no idea how it got there. These leaders had seen the show in the Georgian Republic (then part of the U.S.S.R.) and decided to bring it to their city because they thought people would enjoy it. He said: ‘We thought it would be interesting.’ And he brought his whole family to meet me!”

Anastasia Bliznak, owner of a private museum in the city of Novosibirsk, feels that, for people in her city, seeing Farb’s photographs in the media, and learning that they were in a book, was a revelation and a gift. “I was very enthusiastic when I saw in Facebook the pictures of Novosibirsk citizens from 1977,” she said. “I think that it’s great and that we should be very thankful for this unique large gallery of portraits of the people in our city.”

“One of the pictures in ‘The Russians,’ depicts my father,” said journalist Yakov Samohin. “In 1977, my father was 43 years old. Now he has already passed away. You can understand with what melancholy and love I looked at this photo. Now on my desk is a collage of two photos taken by Nathan, one in 1977 of my father, and another of me in 2018; this is a precious relic for me.”

Svet, the young girl whom Farb photographed, now grown up with daughters of her own, said, of meeting Farb again: “I have a huge joy in the soul from our meeting after 41 years, this time with my daughters! The meeting was like touching one of the pages of the story of my family when my mom and dad were alive. We hugged, burst into tears and talked a lot. It was a meeting dear to me.”