ART MATTERS: The artful guest

I love November.

Hear me out. I don’t love that it signals the end of Daylight Saving Time.

I don’t love that the vibrant fall foliage is replaced by grayscale. My love is not due to the inconsistent temperatures, too cold for lake swimming, not cold enough for winter sports. I love November because some years ago, I decided to turn what I felt was the most challenging time of year into a month of dinner parties. A jubilee of meals, preferably celebrated at dining tables I’m invited to. You’re cooking? I’m free.

Just imagine Eric Carle’s very hungry caterpillar when I say this, “I eat my way through November.”

–

The guest-friendship

–

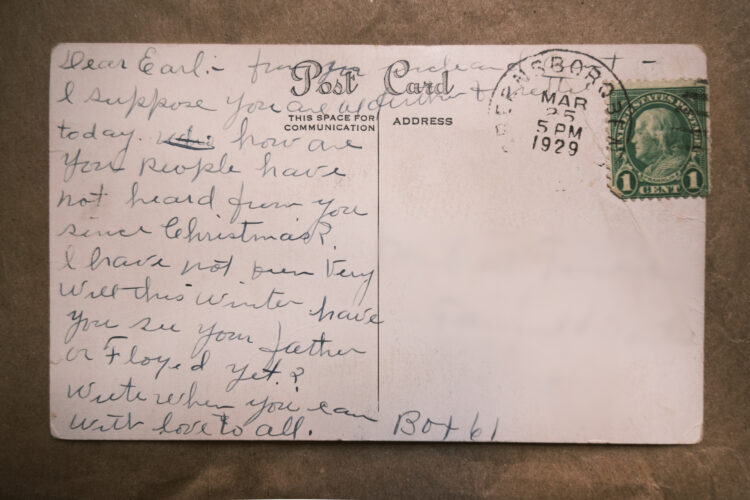

But this column is about art and philosophy and culture, not freeloading caterpillars! So let me tell you about xenia, the ancient Greek concept of hospitality, or more precisely, the practice of being a good guest. The term is often translated as a “guest-friendship,” a notion I appreciate because it rightly implies that there is an innate friendship between the guest and the host, regardless of their preexisting relationship. Tellingly, the word xenia is derived from the ancient Greek word xenos, which means “stranger,” and implies that even strangers owe each other regard when they share a meal. I might not know you, but if I’m your guest and you’re my host, we have a guest-friendship and owe each other kindness.

The principle of xenia is commonsensical. It’s a relationship founded in caring and sharing, good manners, affability, and generosity. Aristotle described xenia as a type of useful friendship, a mutually beneficial relationship that is essential to an effective society. How is a good guest fundamental to a good society? For a political philosopher such as Aristotle, the elements of good citizenship were fundamental to the highest expression of community. In other words, if I can be a good guest (and likewise, if I can be a good host), I’m participating in the meaningful act of building good relations with my fellow citizens. By extension, I’m actively contributing to an ideal society.

Sounds wonderful. Time to eat! What’s that? “Parties can sometimes go to pot,” you say? True. I’ll admit I’m relieved whenever a holiday supper with family isn’t ruined by politics or too much wine, salt, and personality. How, then, do we optimize our chance to have a good dinner party? Let’s focus on our behavior, look to the ancient Greeks for advice on how to be a good guest, and update their parameters for our twenty-first-century lives.

–

How to be a good guest

–

– Be courteous: Show up on time and dress well. Punctuality matters, and a sharp outfit does too.

– Be gracious: Accept the food and drink that is offered. Nobody likes a picky eater, and nobody likes a picky eater who eats all the best chips.

– Do not burden: Don’t eat too much, don’t drink too much, don’t overstay your welcome.

– Be generous: Don’t show up empty-handed.

– Reciprocate: Engage in the conversation, share stories about yourself. Better yet, make the stories funny.

– Remain honorable: Avoid polarizing conversations and defuse tension.

The last one can be hard. Thankfully, Aristotle had advice for this, too. When it comes to the elements of a society, he contended that an unfair person takes more than their share, while a fair person may voluntarily accept less than their due, even when they have the right to take more. By willingly accepting less, the equitable person shows good character and serves a higher purpose. Aristotle’s ideas on justice and fairness not only apply to a well-functioning society but also to a well-functioning social gathering. At a party, I might have the right to express my opinion on a controversial topic, but I don’t need to exercise that right, especially when the conversation will ruin the fun for everyone. For the sake of the dinner, the community, and the duty of being a good guest, I can prioritize harmony, favor the collective over myself and act with decency.

And what’s the best way to deescalate tension? Aristotle again had advice. He claimed that wit at the dinner table goes a long way. Eutrapelia, also known as the virtue of wit, is the golden mean between the buffoon who talks too loud and too much, and the killjoy who finds fault with everyone and everything. Who is this charming middle ground between the insensitive boor and the humorless bore? The witty raconteur, of course. Tell a good story. Tell a good joke. Be generous. Be fun. Be an artful guest.

Don’t have a joke to tell? You can borrow my daughter’s favorite: Which mushroom smells like poo? Sh*itake! (She’s 10. You’ll forgive her scatological humor.) Now it’s time to eat!

Prompt for next time: What are your favorite holiday traditions?

(Jessic Lim can be reached at artmatters.jessicalim@gmail.com.)