NORTH COUNTRY AT WORK: Inside Lyon Mountain with a mining engineer

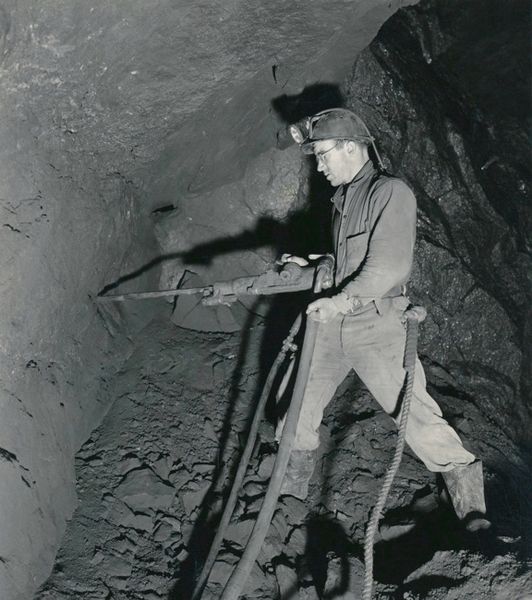

Miner drilling loose ground in mine shaft using an air-pressured drill. The mine was owned by Republic Steel. Circa 1940s. Photo: Lyon Mountain Mining and Railroad Museum

LYON MOUNTAIN – Lyon Mountain’s ore is some of the purest in the world. It was used to build the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

The mine itself was one of the deepest in North America, with its deepest shaft reaching 3,100 feet. The ore was first mined from the surface in the 1860s, then quickly went underground. The town’s population skyrocketed to nearly 3,500 people at its peak, as small settlements sprung up around the mining operation. During World War II, it was the largest employer in Clinton County.

Today Lyon Mountain has fewer than 500 residents, and the mine – Chateaugay Ore & Iron Company, run by Republic Steel starting in 1939 – was closed in 1967. You can, however, still see piles of tailings on the mountain, and the Lyon Mountain Mining and Railroad Museum has a plethora of old photos, tools and machinery from when the mines were cranking.

That’s where I met Jane Kelting, director of the museum, as well as Allen and Jean Caswell. She had asked Allen to come in because he worked in the Lyon Mountain mines starting in the late 1940s, right out of high school, and was there on and off until its closure in 1967.

Allen was born in 1930 and grew up in and around the mines. This is how he introduced himself:

“I am Alan Caswell, and I was born in Lyon Mountain, in what they called 82.”

’82’ was a small settlement that sprung up around the number 82 mine shaft. Houses were built around the railroad track that came up out of the shaft and to the main office area.

Allen’s father worked in the Lyon Mountain mines for 47 years. When Allen was 13 years old, his father got permission for his son to spend a weekend with him in the mines while he was building dams in the mine drifts. That’s when Allen fell in love with being underground.

“I liked to explore, so I walked around. I didn’t get lost or anything, but you can hear every drop of water that falls. I didn’t know one direction from another, and if you walked around a pillar, you walked a mile!”

On that first weekend, Allen was walking through the mines with his father when he had a tumble.

“On the way, there was an excavation, a hole, and my feet slipped,” he said. “And I sat down, and the hole was deep, and my feet wasn’t touching nothing. And my light went out, my hat went off. I just worked myself back, grabbed my cord, put the hat on, turned the switch and my light turned back on. I stood up and backed up and see where my father had went around the corner. I’m looking up here, and there are chunks half the size of this room just hanging. And I walked right by my father, and he reached out and grabbed me by the shoulder, and he says ‘Keep that light on the ground! Watch where you’re going! If that falls on you you’re not gonna know it!'”

Allen wasn’t scared – he was hooked. Against his father’s wishes and knowledge, Allen started working for a small diamond drilling company during his school’s summer break when he was 14 years old. He said he looked much older than his age and was able to pass for a young adult. He made 97 cents an hour and helped set explosives and drill until he was outed by other employees for being underage.

At 17, Allen started working in the Chateaugay Ore & Iron Company mines, then operated by Republic Steel. His first position was “timberman” – which meant he helped to install timbering to support mine shafts. Allen always worked underground, and he did a little bit of everything – from blasting ore to breaking it to moving it out of the mines on the same railroad tracks he grew up around.

To get below ground, Allen took the “skip,” which is like an elevator, but on a 63-degree incline. There were two skips: one for the ore (then called Chateaugay Iron) and one for the people, called the “manskip.” The headframe raised and lowered the skips.

The skip was manually operated, and Allen remembers:

“At times if the hoist operator didn’t ease the brake off … it would drop out right from under ya. They would do that, especially to scare new employees.”

“They” were the older workers. Allen calls them old-timers.

“And they always asked you, ‘Nice clothes you got on. If you get killed today can I have them clothes?'”

Allen worked at the mines until he was 20, when he got married to his high school sweetheart, Jean. The same year, he was drafted into the Army. When he got out in 1953, he started working in the mines again.

He remembers one day when he was operating the train that hauled out broken-up iron ore, and there was a flood in one of the levels above him:

“All of a sudden, water and ore and chunks come down and almost bury the motor up. And the chute puller had to come running down the track to see why I didn’t move the train!”

In the commotion, Allen sprained his ankle. He was miles away from the machine shop, but there was a small eating shanty nearby, which had a small telephone in it. He called for a roll of tape, taped up his entire foot over the boot, and kept working.

Allen said injury was a daily occurrence in the mines, but the pay was so good that people were willing to risk it. The mine was open 24 hours a day on three shifts. Allen said some weeks he worked all three shifts, depending on when he was needed.

He eventually became the underground maintenance mechanic, repairing air scrapers and tuggers. He described his job as head trouble-shooter. He said the dark never bothered him, but the temperature swings could be disorienting. In the winter, it was warmer in the mine than outside, and in the summer, it was much cooler.

The work wasn’t steady, especially once the boom of post-World War II construction started to die down. Allen said he worked for Republic Steel for about a dozen years all together, before the mine closed down in June of 1967. There wasn’t much warning.

“I was on a night shift, operating the 22 Crusher. And Roy Robertson and Ed Knox came down and they said ‘shut it down.’ I said ‘I still have ore to crush.’ And they said ‘we said to shut it down and now.'”

Allen stayed on for another year helping a demolition company clear out the mines. He went on to work for mines all over New England, but he and his wife Jean eventually moved back home to the North Country in the early 1980s, and Allen took a job at Gouverneur Talc. He worked there for 20 years and retired in 1996.

Allen and Jane then returned to the Lyon Mountain area, settling to the north, in the Clinton County hamlet of Churubusco. They both call Lyon Mountain their true home.