The art of remembrance

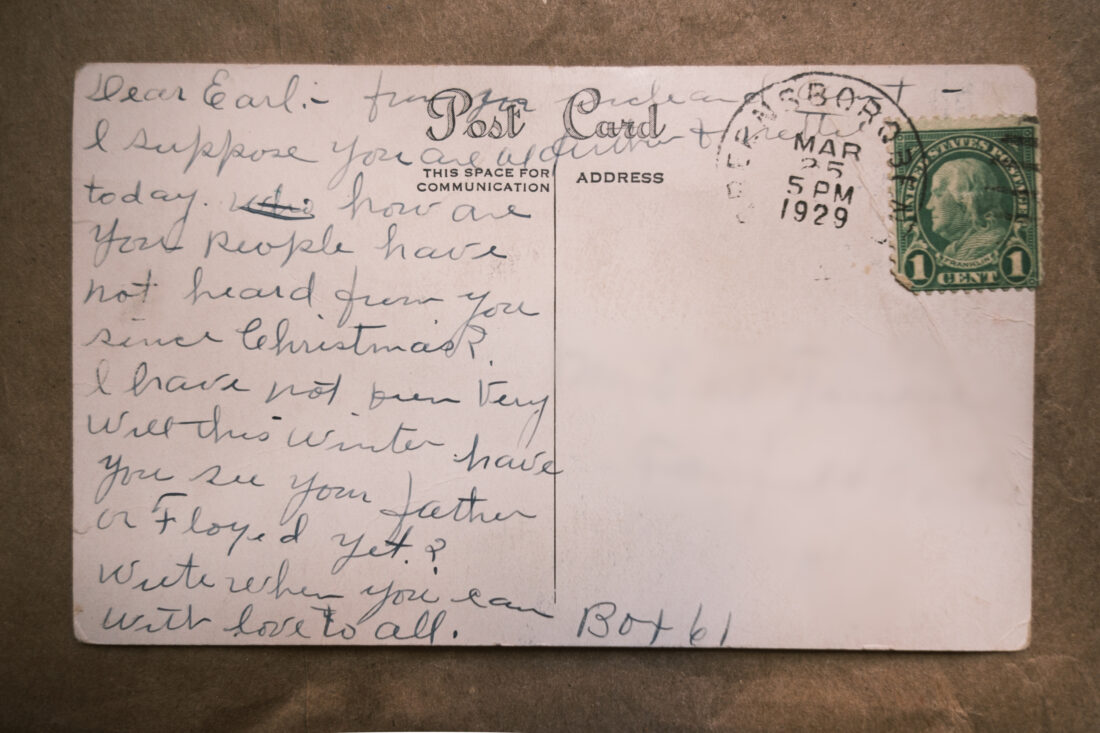

Photo provided by Peter Barra Pictured is a postcard the columnist discovered, written in 1929 from a mother to her adult son.

I doubt I’m alone when I say I want to remember well, not just this month, and not just for myself.

To be certain, I want to remember the day my daughter C was born, the smell of Oil of Olay on my mother’s skin, the first time I plunged into Buck Pond, the sound of P’s shutter; those are my personal memories that I guard jealously, polish in my mind whenever I fear they’ve been tarnished by the passing of time.

But I also want to remember the lives of others — the fallen, those who disappeared, the mothers of the disappeared, the drowned and the saved. I want to remember well because there is something substantive and ethical about it.

–

A duty to remember

–

The writer and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi wrote poignantly about our duty to remember. Memory, according to Levi, serves the dual purpose of preventing the repetition of past horrors and of honoring the deceased. We may not be able to understand atrocity such as fascism, but we have the responsibility to understand where it comes from, and to guard against it in the future. It is therefore everyone’s duty to reflect on the past, to remember it, and to lay the foundation for a better future.

But how? We know that repetition and practice improve our memory, and we base much of our education theory on reproductive learning (i.e., rote memorization and the reproduction of existing knowledge). Yet the type of remembering we do on Veterans Day and Remembrance Day does not involve rote memorization, nor does it always involve preexisting knowledge as many of us pay respect to lives we did not live ourselves. What, then, is involved in the remembrance of Nov. 11, and how do we do it well?

Brendan Bo O’Connor, a neuroscientist and professor at the University at Albany, SUNY, researches the intersection between memory, imagination and empathy. He contends that our willingness to help others and get along with them depends on our capacity to imagine experiences beyond our own. O’Connor’s work explores how the capacity to imagine a shared future serves important functions related to social bonding, empathy and moral decision-making. Collaborative imagining also enhances our ability to conceive and create future possibilities for a family, a town or even a country, he explains.

Similarly, remembrance involves the ability to imagine and empathize with the past so that we can create a better future.

How do we improve at remembrance and how do we teach our children to do it well? O’Connor suggests that imagining a good future is the first step to creating one. Maybe if we practiced the skill of imagining shared worlds, and maybe if we taught our children to practice too, we might improve our ability to imagine and create a better future. Here’s what I tried.

–

Remembrance of

postcards past

–

This summer, I started collecting old postcards. I found them in antique stores, usually in a dusty box, an afterthought in a cabinet of curiosity. One of the oldest ones I found was from 1929 and was written from a mother to her adult son. Like so many mothers before and after her, her message was one of longing and light; emotional blackmail. It had been a while since she’d heard from her son and wanted his news. She vaguely mentioned that she’d been ill over the winter months, but says nothing more about it. The subtext is clear: the severity of the illness will only be known if her son contacts her.

I don’t know this family, and yet I do. We all do. Mothers and sons, fathers and daughters, families everywhere struggling to stay families over growing distances.

I collect old postcards to practice remembrance, to work my imagination into prosocial empathizing. Let me try to remember this mother and her son, to draw on the episodic memory of the postcard, to contemplate it, imagine the world in which it was written, and empathize with the author and readership.

If I can do this for the postcard and do it well, maybe I can also do this for the past in general, maybe I can empathize better in the present, and perhaps I can imagine a future where empathy is our core value, the primary school lesson we teach alongside math and history. Like a pianist who practices scales, or an athlete who drills technique on the field, I try to practice imagining, to drill empathy, to create a new event. I’m working at the art of remembrance, and maybe, as Primo Levi would say, “I’m fulfilling my duty.”

Prompt for next time: What do you do to get through a challenging time?

(Jessica Lim can be reached at artmatters.jessicalim@gmail.com.)